In the serverless paradigm, the idea is to abstract away the backend so that developers don’t need to deal with it. That’s all well and good when it comes to servers and complex infrastructure like Kubernetes. But up till now, database systems haven’t typically been a part of the serverless playbook. The assumption has been that developers will build their serverless app and choose a separate database system to connect to it — be it a traditional relational database or a NoSQL service.

Fauna is challenging this assumption. Its goal is to provide a powerful “data API” for serverless apps, so that developers don’t even need to touch a database system. As co-founder Evan Weaver explained to me in an interview, “we’re decoupling all the back-end operations and service building from the product teams.” This means that everything — including data storage — is controlled and accessible via APIs.

How Fauna Is Different to Other Database Services

Firstly, I asked Weaver how is Fauna’s approach different to Database-as-a-Service (DBaaS) products, like Amazon Aurora and MongoDB Atlas?

DBaaS, he replied, is about “taking the legacy operational model and reducing some of the burden [but] you still have to think about the physicality of the database you provision.”

Weaver argues — in a similar manner to Vercel’s Guillermo Rauch — that developers just want to focus on the frontend user experience of their product. They shouldn’t have to worry about “which Aurora shard I have to query,” as he drolly put it.

So how does Fauna compare to NoSQL solutions? Weaver acknowledged that there are multiple similarities.

“It [Fauna] is a NoSQL document-oriented interface, it’s native to the web, it’s native to JavaScript and the document model [that] application developers are familiar with now and want to use.”

Where Fauna differs from products like MongoDB and Redis, he said, is that it’s serverless, meaning “you don’t have to think about provisioning or shard or VM or replica.” He added that “even if that stuff is managed in the cloud, with Atlas [MongoDB’s DBaaS service] it still exists and still affects your application.”

Fauna also claims it can deliver the transactional functionality traditionally associated with relational database systems. According to Weaver, Fauna has “traditional RDBMS capabilities, but in the web-native service model.”

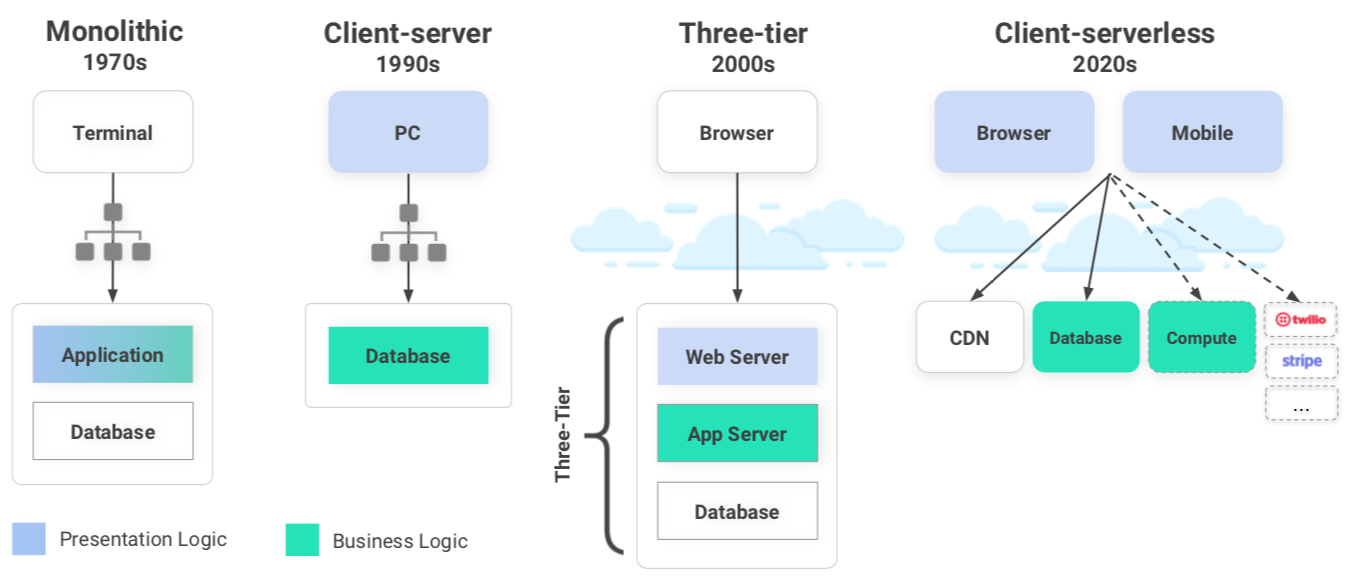

The Client-Serverless Application Model

To support its ambitious claim that Fauna offers the best of both SQL and NoSQL worlds, the company has developed a theory that the tech industry has entered a new era in application development. During the 2010s, the three-tier model ruled — web server, app server, and database. But the 2020s will create a new paradigm, argues Fauna, which it calls “client-serverless.” The following diagram by Fauna illustrates this evolution:

Source: Fauna

“The way we see it,” said Weaver, “it’s a return to the client-server architecture, because everyone has rich clients in their pocket now — their laptop, their mobile — […] and we have front-end product oriented frameworks, like you were talking about in your article about Vercel, that let developers who don’t have that experience in managing cloud services [and] managing three-tier systems still build a full featured and complete product.”

According to Weaver, the three-tier model “is not good enough anymore for your typical developer,” because “people expect essentially a consumer level of product polish in whatever they interact with — you have to ship a progressive web app, you have to ship to multiple mobile platforms, it has to look good.”

Before he co-founded Fauna in 2012, Weaver was Director of Infrastructure at Twitter from 2008-2011 — a period when Twitter was scaling rapidly from a nerdy niche product to a mass consumer one. Weaver was employee number 15 at Twitter and a few times in our conversation he harkened back to his experience from that time, mainly to highlight how much has changed for developers over the past decade.

“The Twitter alpha was rounded corners on a text area,” he said. “Like, that was it. We did that and we thought we had a business going. And you can’t do that anymore — you have to really build. That’s why the three-tier, managed cloud stack has been essentially rejected by this new generation of developers, who have grown up using the browser or [they’re] tired of all the DevOps heavy lifting they have to do to get anything done in managed clouds. They’re now going back to this client-server model — which we’re calling client-serverless, because the big differences are the clients are global and they consume global ubiquitous APIs.”

APIs All the Way Down

In last week’s column, Amazon Web Services developer advocate Nader Dabit said that APIs are the number one use case for serverless. As noted already, APIs are also key to Fauna’s product offering. Most importantly, the way you access your data in Fauna is through APIs. It has a GraphQL interface, along with alternatives such as a “DSL-like functional query language.”

But Fauna also connects to a whole ecosystem of third-party services via API, such as Stripe for payments.

“One of the things that’s interesting about this [serverless] world is that you can compose these vertically integrated services directly, in a way that you couldn’t really do in the three-tier architecture,” Weaver said. “So one of the things that makes it more productive is that you can take something like Stripe off the shelf. Just wire it into the front end and be done, for your billing component.”

It may appear, then, that you can do almost anything in serverless by just connecting together all these API services. But we shouldn’t forget that serverless is ultimately about focusing the developer on what they do best: building applications that are unique to their own business requirements.

“This doesn’t negate the need for the basic building blocks of the application stack that we’ve always had,” Weaver explained, in reference to the ease of connectivity to third-party services. “We’ve always needed an application environment and runtime […] we’ve always needed packaging and delivery, [and] you still need a database.”

In other words, you must still create your own application — and typically you need a database to store the data unique to that application.

As the diagram below shows, Fauna believes it can become a central piece of the serverless ecosystem. But it remains to be seen if the serverless database concept becomes widely adopted, or whether developers will opt to stick with SQL, NoSQL, or DBaaS options.

Source: Fauna

The big, underlying question is: do developers really want to abstract away the database, as well as the infrastructure? It seems more likely, at least in the short to medium term, that most developers will continue to want that extra level of access control and security that a traditional database system provides.

Amazon Web Services, MongoDB, and Redis are sponsors of InApps.

Feature image via Pixabay.

At this time, InApps does not allow comments directly on this website. We invite all readers who wish to discuss a story to visit us on Twitter or Facebook. We also welcome your news tips and feedback via email: [email protected].